Published April 19, 2019 | Updated February 18, 2021 | 6 minute read

I've lost count of the times a senior leader at one of my client organizations said to me “agile won’t work here.”

I’ve heard a lot of:

- “It’s all well and good for tech startups, but it won’t work in our [highly scrutinized/political/regulated] environment.”

- “Teams are a great, but who’s actually accountable?”

- “People need managers.”

- “We’ve tried to empower people before and it was a mess.”

- “We can’t trust front line team members to make decisions, they don’t have the expertise.”

- “We have a Scrum meeting, so we’re already doing it.”

I get it. I work primarily with government and nonprofit clients and there’s a disconnect. The most visible examples of agile organizations are in software (Spotify), e-commerce (Zappos), banking (ING), and other sectors that can feel a world away.

Yet, I see my clients struggling with the same issues: The amount of complexity and uncertainty is overwhelming; decision making is muddled and slow; the needs of the client/constituent feel distant from the heart of the organization; people have to work against the formal org structure in order to get things done.

Why the resistance?

I suspect that the resistance to agile ways of working comes from a false belief that there’s only one way to create organizational agility.

Leaders see the case studies out there and think that agility = hundreds of small, autonomous self-managing teams working on the rapid release of new features. They’re right that this model doesn’t work for all organizations. But the core principles, practices and mindsets of agility can, and not always in the way you think.

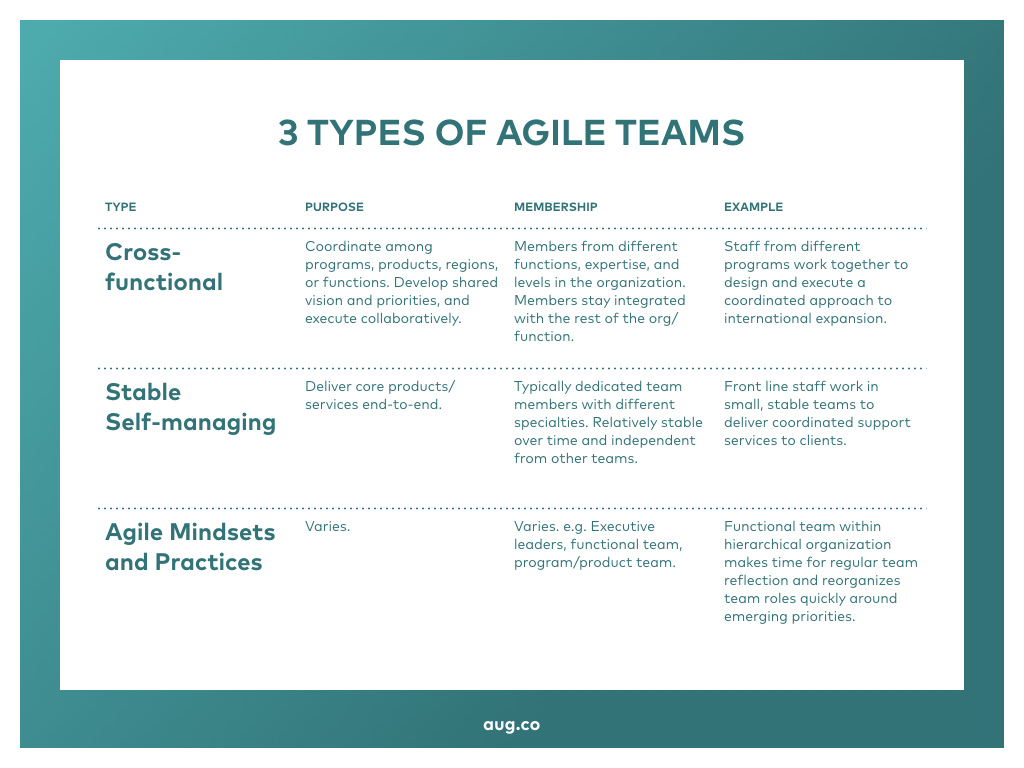

Three type of agile teams

In my experience there are at least three different ways for organizations to become more agile:

- Cross-functional teams

- Stable self-managing teams

- Agile mindsets and practices

Type 1: Cross-functional teams

Cross-functional teams are composed of people from different functions, expertise, and levels in the organization working towards the same objective. While the team lead should be fully allocated, other members could be part-time if necessary. All members should continue to be integrated with the rest of the organization and their function.

Cross-functional teams can be a powerful way to coordinate among programs, products, regions, or functions, develop shared vision and priorities, and execute collaboratively.

They can also get super stuck when they’re operating alongside a vertical structure with a hierarchical approach to decision-making and prioritization.

What does a cross-functional team look like in practice?

I worked with a organization that has a dozen core programs, each of which has an international component. Their strategic plan named international expansion as one of their top 10 priorities. In light of this priority, the CEO sensed an opportunity to increase coordination across the international work and find efficiencies in execution, so they created a cross-functional International Team.

What worked?

- The team met weekly to develop an overall vision for international work

- They created a long-term strategy to increase the organization’s international footprint

- They created a joint implementation plan, which reduced redundancies, saved on travel expenses, and aligned to the overall strategy

While the team made good strides, they also struggled.

- Who had the final decision-making rights? The Team Lead? The CEO? The leadership team?

- Could a program leader veto a new proposed activity if they didn’t have the capacity to deliver it on their team?

- Where would the new team members dedicated to international work sit in the vertical org chart?

- How closely should the team be monitored and given feedback?

Cross-functional teams can be given the best chance to succeed by:

- Creating a team charter that outlines a clear and compelling purpose, time-bound priorities, roles, and norms

- Making decision rights explicit and cultivating a culture of decision-making that values trust, information-sharing, and collaboration

- De-prioritizing other work to allow team members to focus on the cross-functional work

- Scheduling regular demos with the Executive Leadership Team to create an environment of high motivation and high accountability around the work

Type 2: Stable self-managing teams

These teams are composed of dedicated team members, typically with different specialties, and are relatively stable over time. Their purpose is typically set by leaders, but they decide for themselves how to prioritize their work, allocate their time, and are jointly accountable for their goals.

Stable self-managing teams are a powerful way to deliver core services for stakeholders/constituents and cultivate a highly engaged workforce. These autonomous teams get smarter together over time, share leadership, and self-correct when they get off course, reducing the need for managers to control, direct, and constantly steer the work of the team.

They can also get stuck without a clear sense of purpose and effective collaboration. Without internal leadership capacity as well as coaching and support from outside the team to cultivate good habits for collaboration, teamwork can get tough.

What does a stable self-managing team look like in practice?

I learned about an nonprofit that transitioned field staff working as independent specialists to become a nested set of small cross-functional teams where specialists from different functions share a common case load and coordinate supports for the programs they serve. The specialists work together full time on the team, coordinate site visits, share data, collaborate on communications, and reflect together on a regular basis.

What’s exciting about this?

By working together as a stable, self-managing team, these groups are designed to increase the quality and coordination of support while also increasing team autonomy and learning. This is the magic combination. The shared caseload reduces the need for each specialist to communicate with countless other specialists.

What could be challenging?

- Transitioning from a loosely connected network of specialists to small stable teams is a big change. The structure alone won’t change practice and culture. These teams will need to intention and support to cultivate new mindsets and habits.

- Building a collaborative practice takes time, and that can feel like time away from doing “the work.” Without top-down changes to their schedule and total case loads to create time for connection and conversations, this could be an insurmountable challenge.

Stable teams can be successful if they are supported by:

- Setting aside time to understand each member’s role and strengths

- Providing outside coaching for individuals and teams

- Building in regular time for planning and reflection

Type 3: Team with agile mindsets, principles, and practices

This is any team integrating agile ways of working into their workflows, processes, meetings, tools, and collaboration.

An agile team is one that delivers in rapid decision and learning cycles, embraces a bias for action, ritualizes reflection and learning, shares information transparently, and puts clients/constituents needs at the heart of their efforts. This doesn’t have to look any one specific way, but it does have to come from a shared belief that working this way creates more value in the world.

What does a team with agile mindsets look like in practice?

I recently worked with a functional support team of 15 people inside a large organization that surprised me with their commitment to agility, despite operating inside a relatively traditional org structure. They had been working in a quasi-matrix, embedding their people inside other teams across the organization, but were struggling to respond quickly enough when needs of the organization shifted quickly around them. The team prioritized learning through regular retreats and retrospectives that were designed by the team members themselves. They normed around making decision-rights explicit and as close to the work as possible. They started using Slack to increase information sharing and ambient awareness of each other’s work. They created an internal self-managing team focused on system improvements. And most boldly, when their organization’s priorities changed twice in the time I was working with them, their leader quickly reorganized team members into new roles in service of the most critical work streams.

These changes took little more than a reprioritization of this team’s time, a widely available technology platform, and willingness to make decisions and allocate their resources in service their mission.

Conclusion

There’s no one right way to “do agile.” There are many different ways it can look inside your organization, from increasing agility at the center of your organization by bringing agile mindsets to your leadership team, to increase agility at the edges by creating ways for front-line workers to collaborate across boundaries.

The next time I hear a leader say, “that won’t work here” I’ll ask them to step back and look around for ways they may already be agile, and build from there.

.jpg)