Published August 6, 2024 | Updated October 8, 2024 | 12 minute read

Trust has risen to the top of many organizational priorities in recent years.

Leaders are asking big questions about how to build deeper trust with their teams, in order to spark innovation, boost engagement, and cultivate a better employee experience.

But while plenty of leaders, including DEI leaders, are talking about how building trust can improve equity and inclusion, few seem to be flipping that conversation and talking about how equity and inclusion can help build trust.

In light of the recent backlash against DEI across the United States, and the resulting retreat of corporations from DEI as a cultural priority, now is an especially crucial moment for organizations to reckon with the way their own commitment – or lack thereof – to diversity, equity and inclusion is impacting their ability to build active trust.

At August we advocate for our REAL Trust Cornerstones – Reliability, Empathy, Authenticity and Logic – as the central formula for building active trust.

But to effectively build each cornerstone, we need to understand how they operate along the lines of bias and privilege.

Here’s how each REAL Trust Cornerstone can be impacted by systemic and implicit bias, and what you can do to mitigate those impacts in order to build a culture of REAL Trust.

Bias distorts our sense of others’ Reliability

Years ago, as a young Black woman working in nonprofit fundraising, I had a harder time than my white peers at winning the trust – and the donations – of our wealthy white donors.

This wasn’t just an implicit racial or gender bias (although that was certainly part of the problem). This was also a cognitive bias that was explicitly acknowledged by organizational leadership.

“It’s not personal – the donors just trust them more,” my bosses told me when I questioned why my white colleagues were being promoted more at fundraising events.

Cognitive biases are subtle, and usually unconscious – but they can drastically influence who we perceive as Reliable or not – regardless of the person’s character, capability, or track record.

Cognitive bias can take many forms, including familiarity bias – a bias towards familiar options and information, even when unfamiliar ones might be better – or affinity bias – a bias towards people who share our personal interests, experiences, and backgrounds.

Cognitive bias is why white male leaders promote other white men over equally (or more) qualified women and candidates who are Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC).

It’s also why non-native English speakers get fewer professional opportunities in English-speaking companies, despite the advantages of their multilingualism.

Leaders can break the pattern of cognitive bias through a practice called perspective taking.

When you catch yourself withholding trust from someone based on pure instinct, start intentionally asking them questions about their point of view.

The goal of perspective taking isn’t to find common ground, but simply to learn more about how the other person experiences the world.

This intentional pause can help you interrupt your own biases, bridge the cognitive trust gap, and help you appreciate the expertise of people who are different from you.

Cultural biases create barriers to Authenticity

Someone born and raised in the U.S. might naturally be biased towards Western codes of trustworthiness. Direct communication and transparency resonate with their cultural values of free thought, entrepreneurialism, and self-determination.

But someone from a different culture might perceive trustworthiness in terms of a person’s deference and restraint. They might see the U.S. native’s directness and explicitness as a lack of respect, and immediately distrust them because of it.

In turn, the U.S. native might judge their indirectness as a lack of honesty, and distrust them right back!

Our individual Authenticity, in short, can make other people uncomfortable.

And if we make the mistake of conflating trustworthiness with “how comfortable someone makes me feel,” then we will only trust people whose Authenticity directly aligns with our own.

This can make it even harder for professionals who identify as BIPOC, LGBTQIA, and neurodivergent to be perceived as “trustworthy.”

These employees often feel pressured to code-switch, mask, and stay in the closet, which can lead to burnout, turnover, and lower company trust overall.

To mitigate this risk and start building trust across a broader spectrum of Authenticity, organizations can employ the tool of culture mapping.

This framework by Erin Meyer can help team members visualize their individual and collective perceptions of trust, and get more explicit about how they intend to build trust going forward.

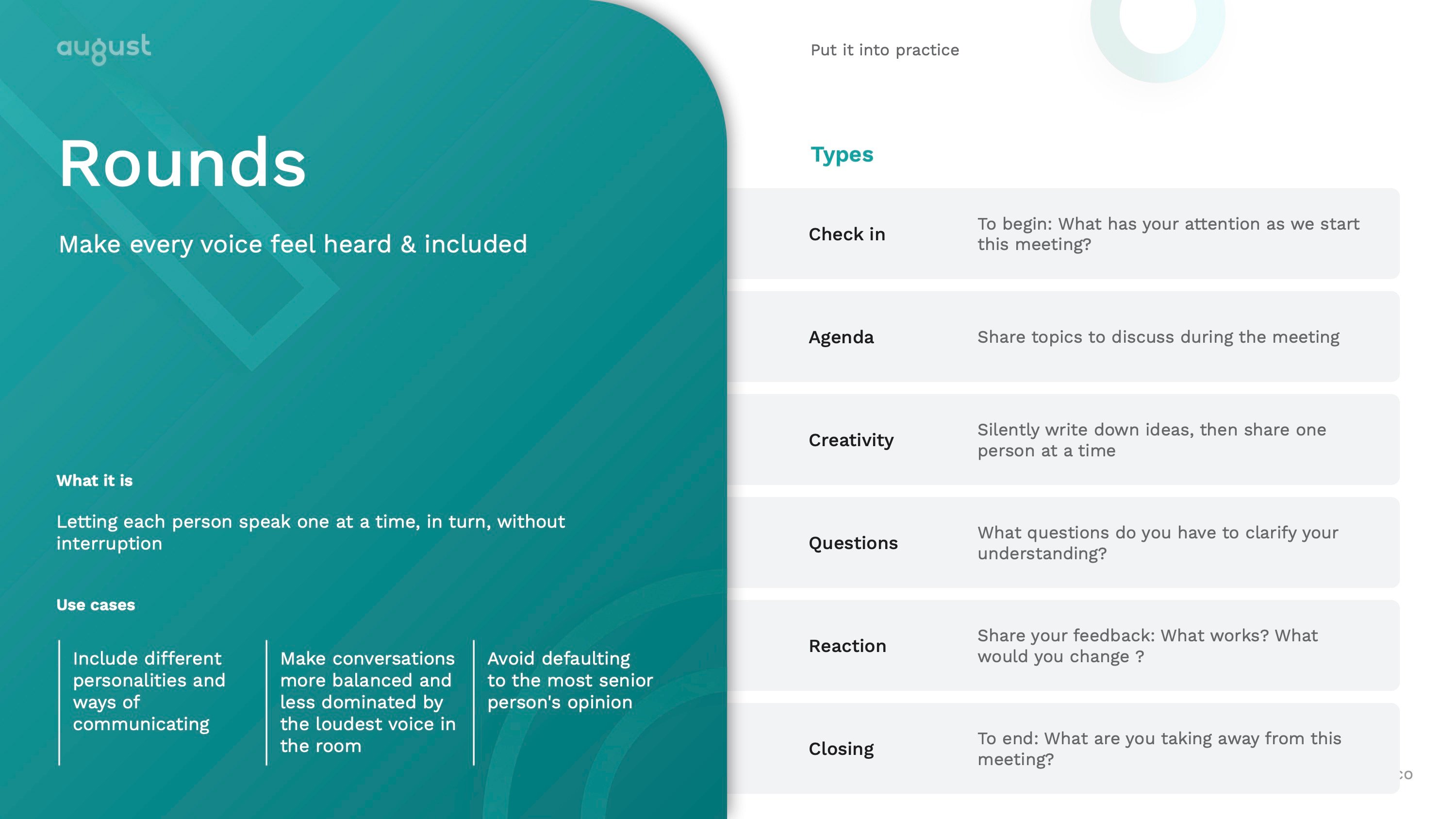

From there, leaders can embed modular trust-building practices into everyday work. Adding a check-in round or a team agreement to an existing work cadence can have a sizable impact on building trust across cultural differences.

Sexual orientation and gender biases shape our access to Empathy and Logic

Of the four Trust Cornerstones, Empathy is stereotypically seen as the most “feminine,” while Logic is arguably seen as the most “masculine.”

Should we be surprised, then, that Logic-driven industries like law and finance carry more prestige and better pay than Empathy-driven industries like nursing and education?

Men themselves are often perceived as being more Logical than women, simply by virtue of their gender. This undoubtedly contributes to men’s higher rates of senior promotion, and their higher salaries.

For decades, the prevailing advice to women was to “lean in” to masculinized expectations in order to level the playing field.

But nowadays, there’s a growing awareness that for many women, “acting like a man” in salary negotiations and leadership roles can actually have a negative impact on how they are perceived.

The truth is there have always been steep trust penalties for anyone who is perceived as behaving outside of gendered expectations.

The more pronounced their departure from conventional gender norms – including how they practice the Logic and Empathy cornerstones – the less trusted they become.

LGBTQIA professionals – especially those who identify as trans, nonbinary, or genderfluid – know this all too well, although their experience is far less studied than that of cisgender women.

This gender-based trust discrepancy is a big, systemic problem that organizations need to address. An easy way to start is simply tracking speaking time in meetings.

Cisgender men dominate the airtime in most meetings, but with the help of AI meeting assistants, it’s easier than ever to identify these patterns and figure out who needs to be heard.

From there, you can use practices like Rounds, Check-Ins, and Amplification to rebalance the scales.

Proximity to power influences our perception of Logic

A former colleague of mine, who is a woman of color, told me about a time when she stepped into a role previously held by a white man ten years her senior, only to find herself being questioned and nitpicked at every turn by senior leadership.

She was carrying forward with the exact plans her bosses had approved for her white male predecessor. The only thing that had changed was the race, age, and gender of the person leading the way.

The Trust cornerstone of Logic is grounded in a person’s credibility, expertise, and communication skills, which my friend had in spades.

However it was clear that her new bosses perceived her Logic as less than her predecessor’s, who had a much closer proximity to structural power and social identity power than she did.

As biased humans, it’s common for us to gauge a person’s Logic according to their proximity to power. Most of the time, we don’t even realize we’re doing it!

This can be overt, as in the case of my friend, or subtle, as in the case of accent bias.

In English-speaking contexts, people who speak English with a “native” accent (e.g. British or American) are perceived to be more trustworthy than people who speak with a “non-native” accent (e.g. African or Middle Eastern).

This presents a significant barrier to trust for members of the Global South, who are perceived as less Logical – and therefore less trustworthy – than their “white-sounding” counterparts.

In order to start building trust across these social power differences, leaders must take a long, hard look at the implicit standards of credibility that govern team cultures.

Who is getting promoted? Whose word is trusted? Who is being silenced and sidelined? Whose voice is not being heard?

It can also be helpful to examine your team demographics through an equity lens, to discern who is most likely to experience barriers to trust based on the identities they hold.

Summary: Trust requires equity and inclusion. They can’t be separated.

I am a big supporter of the current push for greater organizational trust. I think it’s an important step towards building more effective, responsive, human-centered organizations.

But the work of building trust can’t be separated from the work of building equity and inclusion.

The two are deeply linked. Strengthening one will lift the other. But ignoring one will damage both.

When implicit biases skew our perceptions of each other’s Reliability, Empathy, Authenticity, or Logic, it damages the entire organization’s capacity to build active trust in a sustainable way.

But when leaders strive to build trust through the lens of diversity, equity and inclusion, they cultivate a deeper culture of trust for everyone in the organization.

Learn more about how August helps organizations operationalize equity and inclusion. If you'd like to explore partnering with August on building trust, please reach out!

.jpg)